How well do you know your neighbours?

Some people refuse contact with neighbours even when they live in adjacent houses / apartments.

Do you know your neighbours? I don’t. I have been living in the same apartment for three years, but haven’t exchanged a word with my neighbours. Wonder why?

Let me explain. I’m kind of an antisocial. Don’t make friends easily, and don’t talk to strangers. An antiseptic smile is the best I can manage. Prefers to keep to myself and stick to the same circle of friends and relatives. Well, you can call me an introvert. That would explain my lack of interaction with neighbours.

My wife’s exactly the opposite. Yet, she has failed to strike up a conversation with the occupants of the flat across the corridor. The doors face each other. At times, we open the doors simultaneously, and the elderly lady behaves as if we don’t exist. So do the two young adults. We hardly get to see the other neighbours.

How young children make a difference

================================

Maybe they want to be left alone. I understand that. Yet, it feels strange. Weird, actually!

Humans, they say, are social animals. Our lives are interlinked and interdependent in some way, especially when we share a building. The blank stares and the radio silence in the elevators baffle me. Isn’t this a community? I ask myself.

I lived in another apartment for 20 years, and the experience was totally different. We had plenty of friends in the building and the neighbouring blocks. Some of those friendships exist even today, even after they have moved to other countries.

Much of the indifference may be due to big-city syndrome. People are so busy with their lives that they don’t have time for socialising.-

What’s the difference? One reason was our children. They were young and had plenty of friends. I remember a time when the doors of three neighbouring flats, including ours, were never locked as children kept moving from one house to another to continue their games. That was when my daughter was a toddler. At least 25 children in the neighbourhood would attend my son’s birthdays.

The children’s parents became our friends, and we called on each other for festive occasions and pujas. Sweets used to be sent and received during Diwali. Help used to be sought and given. Seems like another era.

Even after we moved, my wife maintained friendships in our old neighbourhood. She frequently travels there to attend birthdays, pujas, picnics, and other community activities. I often tease her, saying that her social skills haven’t worked in the new neighbourhood. She shrugs it off, saying it takes two people to strike a friendship.

Much of the indifference may be due to big-city syndrome. People are so busy with their lives that they don’t have time for socialising. When you get home from work late, visiting the neighbours is the last thing on tired minds.

What about weekends and holidays? Plans would have been made weeks ahead, and grocery shopping and prayers at a temple or a church are a weekend phenomenon. In homes where husbands and wives work, Saturdays and Sundays can turn into marathon cooking sessions to cover the week. All that doesn’t leave much time for neighbours and friends.

In many cases, it’s down to privacy. People value their privacy, which is why they keep to themselves. Imagine if your neighbours are nosy parkers. They could make lives miserable with incessant questions and the insatiable curiosity to know everything that happens in the neighbourhood.

None of us would want that. Right? Then why am I complaining?

You don’t have to take the biblical phrase “Love Thy Neighbour” literally. A little bit of social contact between neighbours wouldn’t hurt. And you don’t have to be friends with all the neighbours. A hello, a good morning, a smile, or a nod would suffice.

Do I do that? Yes, I do. Especially when I’m riding the elevator. It feels good when others return the gesture. A smile is the best. So keep smiling.

=================================================

New Year, New Questions You Won’t Solve!

I get smaller every time I take a bath.

What am I?

Do you think you know the answer to our daily riddle? Don't spoil it for your neighbours! Simply 'Like' this post and we'll post the answer in the comments below at 2pm.

Want to stop seeing riddles in your newsfeed?

Head here and hover on the Following button on the top right of the page (and it will show Unfollow) and then click it. If it is giving you the option to Follow, then you've successfully unfollowed the Riddles page.

Clothesline upgrade

Turn a tired old clothesline into a stylish garden feature that brings joy to the chore of getting your washing out in the sun. Finish in Resene Waterborne Woodsman Crowshead. Find out how to create your own with these easy step by step instructions.

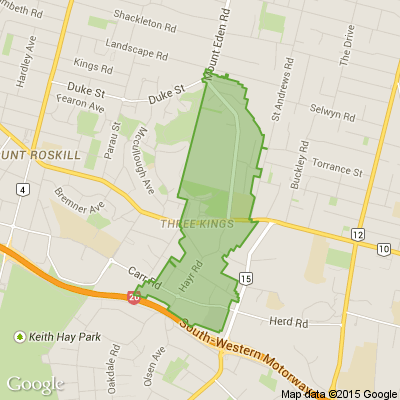

Explore more, worry less at Ryman

Pack your bags, hit the open road, or set sail on your next big adventure. With Ryman’s lock-and-leave-style living, you’re free to explore without worrying about home maintenance or security.

While you’re off enjoying life, we’ll take care of everything back home – from mowing the lawns to watering the garden, pulling weeds, and even cleaning the windows.

Ryman residents are free to embrace adventure because they're not tied down with home maintenance stress and security worries. They're rediscovering lost passions and plunging headfirst into new ones whenever they feel like it.

Click find out more to discover the lifestyle.

Loading…

Loading…